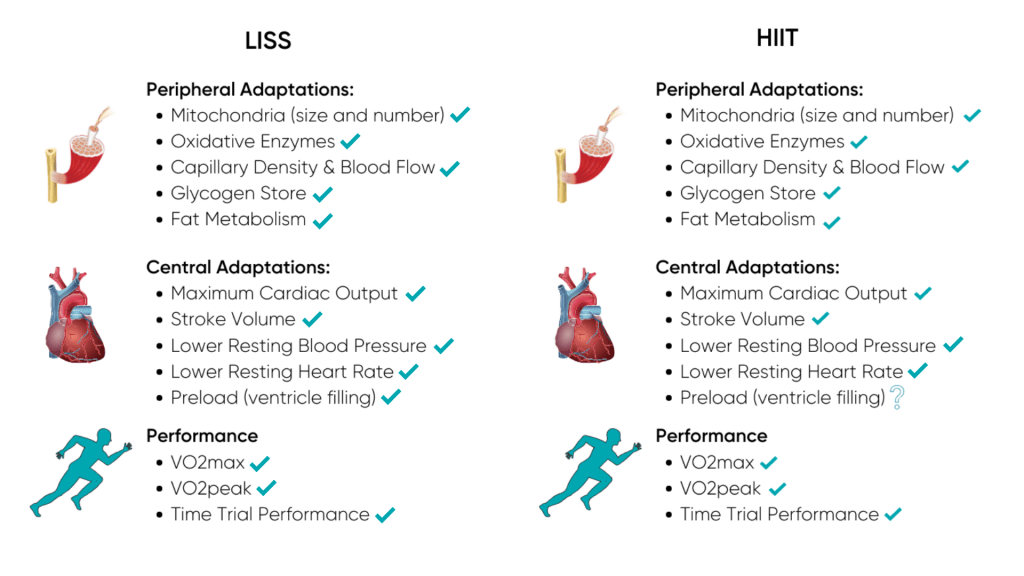

Martin Gibala and Martin Macinnis are the most prolific HIIT scientific researchers in the game and upon a review of the HIIT literature as a whole (20), here’s what they had to say:

“Exercise intensity is a key mediator in mitochondrial adaptations, which could, in part, explain the observed improvements in VO2max scores relative to moderate intensity continuous training. HIIT seems to elicit these adaptations to a higher extent when training volumes are equal, and to a similar extent when HIIT volume is lower. Evidence of other physiological adaptations such as capillary density and cardiac remodelling is emerging, but still equivocal.”

They go on to summarise:

“Interval training is a powerful stimulus to elicit improvements in mitochondrial content and VO2max; however, we know relatively little regarding the influences of exercise intensity, duration, and frequency on other components of the integrative physiological response to interval training”

Superior Energy Expenditure – The Afterburn?

HIIT is often sold as a workout in which you burn huge amounts of calories, not only during but long after the session. It is therefore assumed that your metabolic rate will ramp up and you’ll turn into a fat-burning furnace! Like most things, this isn’t necessarily false but regretfully, this seems to have been grossly over-exaggerated and it’s important to put the actual numbers into context.

This “afterburn effect” is known as Excess Post-Oxygen Consumption (EPOC), which is essentially an energy debt that is built during intense exercise and paid back afterwards. Exercise duration has a positive linear relationship with EPOC, but this only really seems to take effect when you hit a certain intensity, around 60% VO2max (2,3,15).

It has been shown that EPOC is significantly higher following HIIT, compared to volume matched low-intensity continuous training, the magnitude of this statistical significance fades into somewhat insignificance when put into a real-world context.

Here’s a nicely designed study (21) that illustrates my point:

Study Design:

- Participants had their oxygen consumption and energy expenditure analyzed.

- This was assessed every few hours over a 24-hour period, including for one full hour during which participants rested or exercised.

- During that hour, they either

1) Rested for the entire hour.

2) Rested for 10 minutes and then cycled for 50 minutes continuously at a moderate intensity, or

3) Rested for 40 minutes and then did 10 x 60-second high-intensity cycling intervals with 60 seconds rest in between.

Results

During those one-hour periods, here’s the average number of calories they burned:

- Complete Rest: 125 calories

- 10min Rest and 50min cycling: 547 calories

- 40min Rest and 20min HIIT: 352 calories

Over the full 24 hours (including the exercise period), here’s approximately how many calories they burned:

- Complete Rest: 3005 calories

- 50min cycling: 3464 calories

- 20min intervals: 3368 calories

So as you can see, you could say that the HIIT protocol was more time-efficient for a similar 24h energy expenditure, but remember the exertion of the 20min HIIT will have to be significantly higher than the 50min LISS.

Be Smart When Training Hard

Exercise modality is a variable that should be taken into consideration when performing HIIT. Skill requirements should be low, as technique will suffer when fatigue kicks in. Far too often people sacrifice technique for the sake of intensity, don’t be this person! To get the most out of this type of training, use a simple exercise modality (ride, run, row etc).

In general, it’s probably not wise to introduce externally loaded resistance training when performing this type of training. Unless your technique is very well ingrained, almost second nature. Only then, should you introduce high amounts of fatigue (akin to the best CrossFit athletes).

Summary

HIIT can be a potent tool used to improve your fitness and burn calories and occurs mainly by trading intensity for duration. HIIT seems to elicit similar outcomes in terms of VO2max and calorie expenditure but requires less time commitment. This trade-off, however, is not for the faint-hearted, as it requires repeated bouts of near maximal effort. Some researchers note that;

“HIIT requires an extremely high level of subject motivation” and question whether the general population could “practically tolerate the extreme nature of the exercise regimen.”

The highly stressful, taxing nature of HIIT requires smart programming, to minimise any negative aspects of fatigue and maximise time for recovery. For this reason, HIIT is usually performed either by itself as a stand-alone session, or at the end of a session, in the form of a “finisher”. Choosing an exercise modality that requires low levels of skill and cognitive processing, allows you to work hard enough without the distraction of technique proficiency.

We feel that a balance can be found between HIIT and LISS. LISS is effective at building an aerobic foundation, to aid recovery and address symptoms of chronic stress. HIIT can be introduced as a time-efficient strategy to improve fatigue resistance at high thresholds. Individual preference, goals and responsiveness will dictate their use for calorie expenditure and specific fitness gains.

For most, however, an appropriate balance of the two is usually advised. If you feel you’re suffering from chronic stress, then perhaps spend a little more time performing LISS. If you’re in pretty good shape and are looking to get as fit as possible in as little time as possible, then get yourself doing some HIIT. Just be sure, the high-intensity aspect is truly high enough.

Common Purpose Team

Common Purpose Team