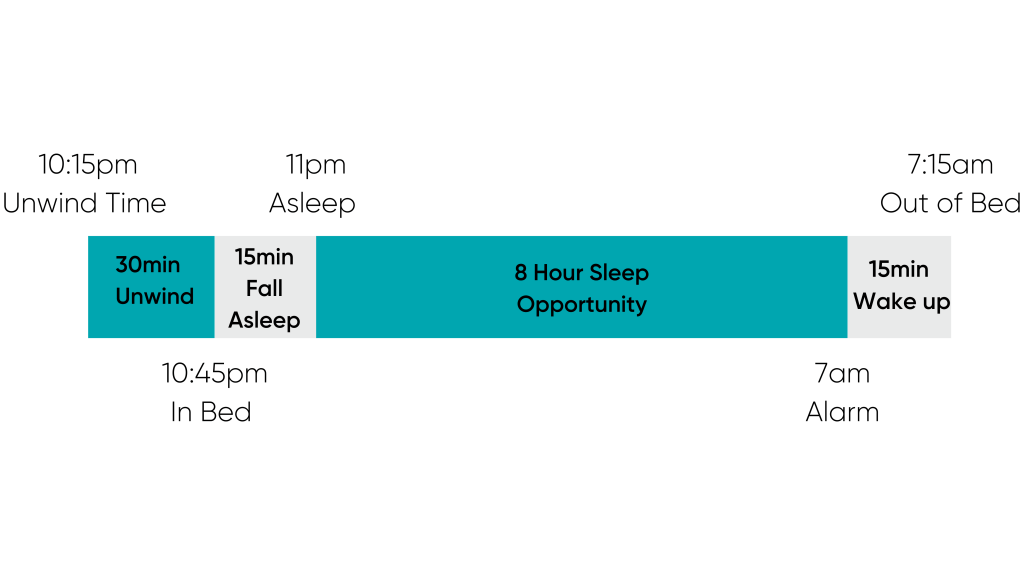

2. Set Aside Time to Unwind

This doesn’t mean sitting on the sofa binge-watching Netflix! This means entering a state which primes your mind and body for sleep. Set an alarm at least 30mins before you want to go to bed and establish a pre-bed routine.

The strategy:

- Turn off the TV.

- Get away from your phone and laptop (this is a notoriously difficult one).

- Turn the lights down.

- Do something relaxing such as breathing, stretching, foam rolling, having a bath, meditating, reading a book, etc.

3. Improve Your Sleep Environment

The environment in which we sleep can have a profound effect on our ability to nod off. Here are some simple rules to follow in this regard to improve the odds of getting a good night’s sleep:

The Strategy:

- The darker the better – light is a stimulant, which your body is very sensitive to, even when our eyes are shut. Invest in thick blackout blinds, keep any light-emitting devices to a minimum and use a sleeping mask if necessary.

- Keep it cool – A gradual temperature drop is another cue your body uses to initiate its sleep mechanisms and sleep quality is much higher in moderately low temperatures. Set your thermostat to a cool, but comfortable 15-20ºC (60-67ºF) at least an hour before bedtime. For those without thermostats or air conditioning, you could invest in a special cooling sleep system (such as the ChiliPAD made by the Chilisleep company), or at least make sure your radiators are turned off at night and crack a window if necessary.

- Keep your bedroom clean and tidy – disorganisation and messiness often reflect in our thoughts, one way to help declutter our internal environments is by tidying up our immediate external environment.

OK so we have our regular sleeping patterns in place, we’ve established pre-bed routines to help us unwind and our sleep environments are cool, dark and tidy the next two recommendations are about two of the most common sleep disruptors we regularly consume; caffeine and alcohol.

4. Adopt a Caffeine Curfew

Now, in an ideal scenario, we wouldn’t need the aid of stimulants to feel awake, but coffee in the morning or before a workout isn’t the end of the world and may even be beneficial to our health and performance.

It’s important to note, however, that caffeine has an average half-life of 5-6 hours (this does vary between individuals). This can mean that the caffeine from your after-dinner coffee/tea/caffeinated soda at 8pm could still be having a significant stimulatory effect until at least 2am!

The Strategy:

- This one’s simple, don’t consume caffeinated beverages beyond 4pm.

- Replace with de-caffeinated alternatives if necessary.

5. Skip the Nightcap

Alcohol can have a detrimental effect on sleep quantity and quality. After a few glasses, or pints, or bottles(!) you may find that you can fall asleep fairly quickly, but experience multiple “mini-awakenings” during the night. This can be the reason you feel so tired and lethargic the next day, a big contributor to that dreaded hangover.

According to the National Sleep Foundation, alcohol reduces the quality and quantity of your sleep in the following ways:

- It activates different sleep rhythms simultaneously, which battle against each other, causing multiple disturbances.

- It blocks REM sleep.

- It’s a diuretic, which means multiple trips to the bathroom!

The idea of the nightcap is therefore paradoxical, and according to sleep expert Matthew Walker:

“Alcohol sedates you out of wakefulness, but it does not induce natural sleep”

The strategy:

- Try not to use alcohol as a means of distressing at the end of the day.

- Try to reduce regular alcohol consumption, staying teetotal for most nights of the week.

- Replace with non-alcoholic alternatives if necessary.

- Replace the routine of drinking with an alternative pre-bed routine previously mentioned, to help you unwind.

Summary

We hope our sleep articles (part 1 and 2), have highlighted the importance of getting good quality, regular sleep of sufficient quantity. The intent of these articles was not to simply tell you to get more sleep but to investigate the reasons why sleep is important, the causal mechanisms between sleep and some select health outcomes, and then to suggest actionable steps towards improving your sleep hygiene.

These suggestions are a good start, but remember that it’s ultimately down to you when it comes to taking your health into your own hands! The evidence suggests that good sleep is non-negotiable, so why not do some experimenting and investigating into your own sleep and find what works for you!

Common Purpose Team

Common Purpose Team