Big Hairy Audacious Goal

We’ve helped many brave souls prepare for marathons all over the world. Each client has unique motivations, histories and needs. As such, we work really hard to meet trainees where they’re currently at and safely develop them to be able to withstand and endure such a long and challenging event.

Although our programs are highly individual, there are a few principles we can apply across the board. These principles have been heavily influenced by the work of Dr Stephen Seiler, a Professor of Exercise Physiology, who is one of the world’s leading experts in endurance training.

Professor Seiler created a hierarchy of priorities that we’ve found to be very practical, thorough and concise. Like all fundamental principles, they can be applied to novice and elite runners alike. Here’s our take on this list of priorities, as well as a case study of how we helped our most recent marathoner!

Priority #1 | Build your Mileage

Increase Training Volume

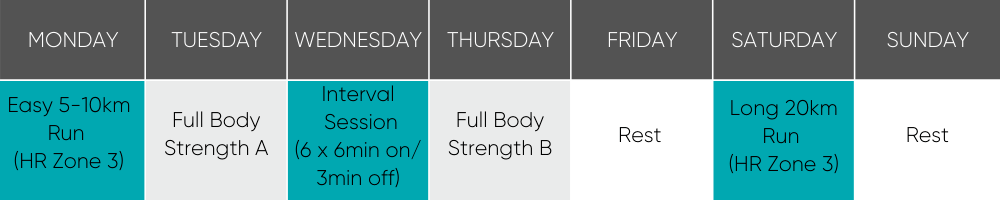

First things first, you need to get your miles in. Research on recreational runners found that weekly running mileage was correlated with their ability to sustain higher running speeds. Even elite athletes see their aerobic fitness (VO2max) improve as they increase running volume. If you’re a beginner aim to build to a comfortable 10-15km. Don’t worry about the pace for now, just aim to do the distance without breaks.

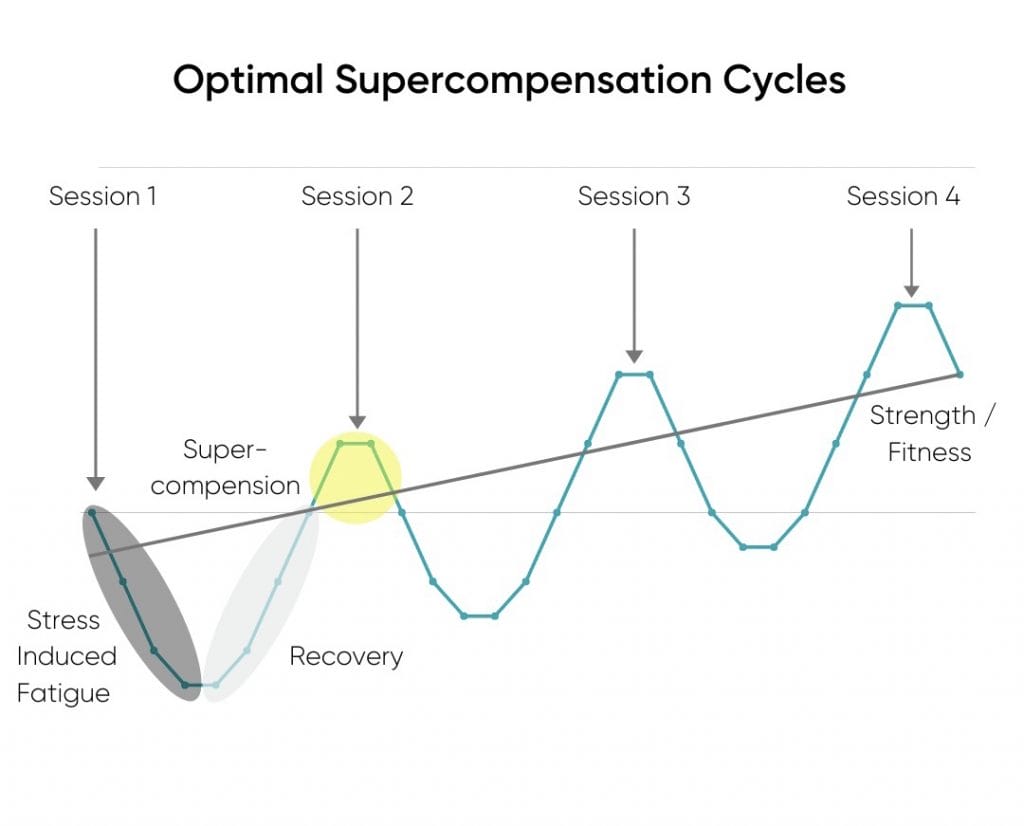

Take Your Time and Build Slow

So it’s clearly well established that increasing training volume is important. This process, however, needs to be a gradual one. As explained in our “Training Through Pain” article, exposure to training stimuli is a bit like sun tanning. You’ve got to slowly build up your tolerance to the impact and stress of running long distances, allowing enough time for your body to recover and adapt.

The biggest mistakes we see, especially amongst first-time marathon runners, is not giving themselves enough time to prepare, going too hard, too fast and ending up injured.

Give yourself enough time to build the miles over the course of your training program, for a beginner going for their first marathons, we recommend a minimum of 20 weeks prep time. Start off low and slow. If you’re already in the thick of it, then a good rule of thumb is to limit your training volume increments to 10-15% per training week (if time allows!).

Utilise Low Impact Activities

Although a large majority (at least 80%) of your training should be spent running, a nice way to increase training volume whilst keeping injury risk low is incorporating different exercise modalities.

Swimming, cycling and rowing, for example, allow you to rack up the miles and hours without overly exposing your joints to the repetitive impacts associated with running. Using these exercises on top of your running to further improve your cardiovascular fitness, may come in handy. These activities are also advised if you encounter an injury. Use them as part of your rehab to retain the aerobic fitness you’ve worked so hard to gain.

Priority #2 | Stay Strong!

This is a key aspect of the “injury-free” component. As much as some endurance athletes dislike it, adequate strength is crucial to protect the joints. In order to tolerate so much volume, you need an equal blend of fitness, strength and technique.

Improving the ability of your muscles to absorb and produce force in a well-coordinated manner does brilliant things for your running economy. Appropriate and relevant strength training should not be overlooked and should be seen as an important supplement to your endurance running training.

Did you know that every single foot strike requires the absorption of 2.5x your body weight?

This doesn’t mean you need to start powerlifting 5 times a week! You just need to ensure that your joints, ligaments, tendons and muscles are both resistant to fatigue and maintain integrity under load. We suggest two full-body strength training sessions a week, focusing on developing the entire lower body chain and midsection.

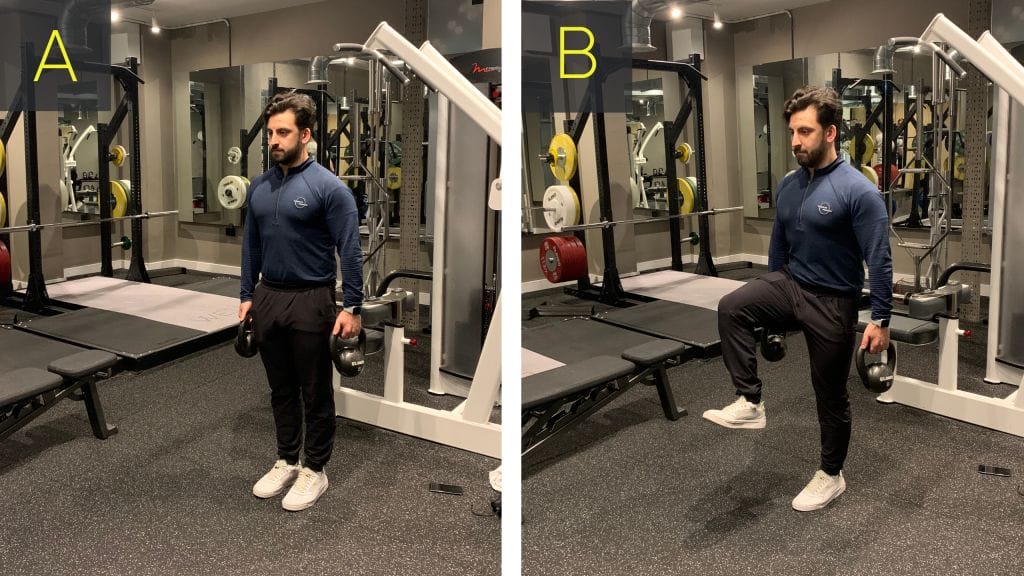

Here are some examples of our favourite strength exercises for runners:

Offset KB Bulgarian Split Squat (click for video)

Common Purpose Team

Common Purpose Team