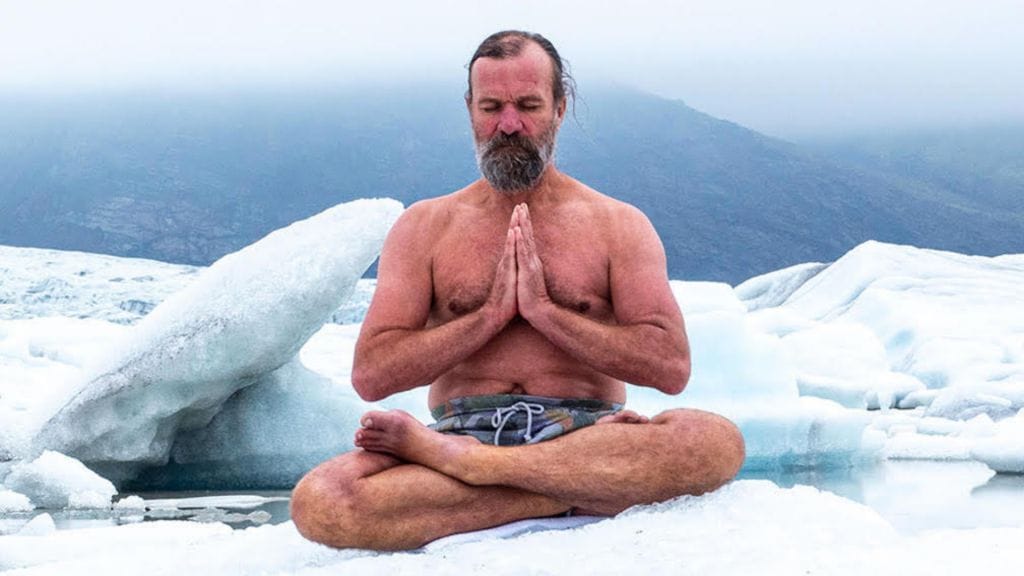

The Benefits of Cold Exposure:

Recovery and Inflammation

This is a contentious topic. The ice part of R.I.C.E (rest, ice, compression and elevation) as an effective strategy for recovery from injury or training has come under scrutiny. The acronym was originally coined by Dr Gabe Mirkin in “The Sports Medicine Book” (1978). Gary Reinhl, the author of “Iced”, puts forward a strong argument against the use of ice as an aid for injury and recovery. This view is now becoming popular amongst physiotherapists and experts in the subject such as Kelly Starrett and Dr Rhonda Perciaville Patrick.

Inflammation is part of the acute healing process. The anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties of ice (once thought to be beneficial) may slow down the recovery process, as opposed to speeding it up. Even Dr Mirkin himself has changed his opinion on the subject, writing on his website:

“Inflammatory cells rush to injured tissue to start the healing process (Journal of American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, Vol 7, No 5, 1999). The inflammatory cells called macrophages release a hormone called Insulin-like growth Factor (IGF-1) into the damaged tissues, which helps muscles and other injured parts to heal. However, applying ice to reduce swelling actually delays healing by preventing the body from releasing IGF-1”

However, Dr Patrick takes this one step further:

“The purpose of inflammation is to eliminate the initial cause of cell injury, clear out dead cells and tissues damaged from the original insult and the inflammatory process, and initiate tissue repair. However, when this process runs awry, in the absence of actual biological threat, we’re in trouble.”

Chronic and systemic inflammation is a cause for concern, which can be to blame for a large array of illnesses, pain and disease. Like most things in biology, it’s all about balance. We don’t want to stop inflammation from occurring altogether, especially in the acute stages of recovery, but if it becomes a chronic issue, health may start to suffer. Regular bouts of controlled cold exposure, therefore, may be a tool we can use to optimise recovery, improve adaptations to specific stresses and reduce the risk of inflammatory-related diseases.

Improved Mood, Energy and Focus

One of the most consistent findings when it comes to cold exposure is an immediate boost in energy, vitality, positive mood, clarity and focus. A recent study has demonstrated that cold showers significantly increase endorphins and adrenaline in the blood and increase the synaptic release of adrenaline in the brain as well! It has been suggested, therefore, that cold showers may be used as a treatment for depression.

Blood Sugar Regulation

In preliminary research conducted on rats, cold exposure has been shown to “improve glucose tolerance and stimulate glucose uptake in peripheral tissues”, therefore aiding to regulate blood sugar levels. With the prevalence and rate of type II diabetes on the rise, cold exposure may be an effective preventative strategy to combat this trend.

Immune System Function

Some studies have demonstrated that cold exposure can act as a potent immunostimulant, especially in conjunction with pre-treatment exercise, possibly due to increased rates of circulating norepinephrine. It has also been shown, for example, that cold water swimmers retain healthier levels of white blood cells in the blood system, which are crucial in the immune system’s ability to fight disease.

Cardiovascular System Function

The cold increases blood pressure, respiration and heart rate, similar to exercise. Exposure to bouts of cold can help circulate the blood around the body and forces the cardiovascular system to effectively pump blood and oxygen to the muscles. A well trained cardiovascular system enables the body to deal with stress better and reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease development.

Weight Loss and Metabolism

When the body is exposed to the cold, it begins to generate heat by increasing its metabolic rate. This is known as Cold-Induced Thermogenesis! Although the magnitude of this effect varies widely between people, brief bouts of cold exposure may help accelerate weight loss (particularly from brown adipose tissue) by increasing overall energy expenditure.

Protection from Neurodegenerative Disease

This is where our cold shock protein friend RMB3 comes into play. Mice studies have demonstrated that early exposure to cold temperatures helps protect against neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and stroke, due to the protective properties of RMB3 on brain synapses. It has therefore been suggested that cold exposure could be used as a promising protective target for therapy for neurodegenerative diseases, although the science is extremely new.

Sleep

Our circadian rhythms use light and temperature to stay regulated. Exposing ourselves to natural changes in temperature, including the cold, can help regulate our sleeping patterns. This is the reason it’s recommended that we sleep in cool environments (as we’ve mentioned in sleep part 2).

Mental Resilience

This one is somewhat anecdotal but psychologically important nonetheless. Setting yourself a challenge like this, overcoming discomfort and learning to control your body’s response under perceived threat can be powerfully rewarding and fulfilling. Not only does your willpower improve but you also get a feeling of achievement and accomplishment.

Tiago

Tiago